By Jean-Julien Aucouturier of J@pan Inc Magazine

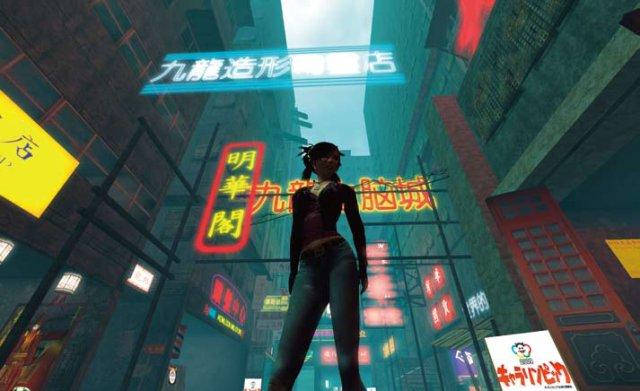

The virtual landscape of Second Life (SL).

By Jean-Julien Aucouturier

With nearly 1.5 million members, could concerts in Second Life be the future of music?

The two artists, both professional musicians, couldn’t be more different.

One is a live-show powerhouse, playing more than 20 sell-out gigs per month. His fans travel from all over the world just to see him, and many have been following him since the early days. In between concerts, they blog about the shows. During the concerts, they tip so fervently that money literally piles up on the stage.

The other is not reaching the audience he deserves. Embroiled in a disproportionate network of industrial interests, his artistic freedom is jeopardized and his music denied radio airplay. His tour manager is fixing abusive ticket prices, which are beyond his control. His current contract rips off more than 70 percent of his potential revenue. Like many of his fellow artists in the same scene, he is incredibly tempted to simply give his music away for free, craving for a way to just reach his audience without all the hassle.

Musicians can reach people they wouldn’t have been able to previously.

The second of these two musicians is the recipient of 19 Grammy Awards, Bruce “The Boss” Springsteen. The first is Komuso Tokugawa, a robot-like 3D avatar who sings the blues in the virtual world of Second Life. Many will resent comparing the author of “Born In The USA” with what is essentially a creature of pixels and bytes. Introduced in 2003 by California-based Linden Labs Inc., Second Life (SL) is a computer-based recreation of the real-world, entirely built by its users—now a thriving community of over 1,400,000 people. Like in a video game, real-life users of SL appear in virtual reality as 3D characters—or avatars—and they can interact with other users’ avatars and their environment. Certainly, there is an irreducible difference between singing in front of the 98.7 million viewers of Super Bowl XLIII, and singing into one’s computer to a virtual audience of a few tens of 3D characters. But the question here is not whether virtual worlds like SL offer conditions for music that are better or worse than, say, the radio or the mp3 before them. The key question is whether the emerging micro-economy of music in SL is a fad or a trend, something so strong maybe as to shape the future of the music industry. Something that technology will have to follow, rather than create.

Playing one’s own music for a virtual audience doesn’t require a lot of technical know-how. With a microphone and an audio interface, one can capture sound live in a computer at home or in a studio, and set up this computer as an internet radio server to broadcast the audio stream to the computers of your audience. If at the same time, the performer is present in virtual reality as his/her avatar, and the audience is too, you’ll get a complete virtual recreation of a gig. This relative simplicity explains in part the formidable popularity of live music events organized in SL. A survey in September 2007 showed that 58 percent of the events advertised on a typical SL day are live concerts and another 38 percent are DJ/Club events.

Interestingly, music in SL is nearly never recorded music; what matters is the live performance. In a sense, this jumpstarts a trend that the real-world recording industry has been resisting for years now: its, well, death.

Interestingly, music in SL is nearly never recorded music; what matters is the live performance. In a sense, this jumpstarts a trend that the real-world recording industry has been resisting for years now: its, well, death. According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) CD shipments in the United States were down 20 percent in 2006, and again down 17.5 percent in 2007—something the RIAA readily attributes to illegal file-sharing on the Internet, but academic research rather identifies as the end of an age. What is under question here is the very value of fixing music on a medium. Leonie Smith, a jazz singer in real-world and a SL TV host by the name of Paisley Beebe, puts it in a deceptively simple way: “In the real world, you might never get to see your favorite musician live. This is why you buy CDs. In SL however, you can teleport out anytime if you want to catch that musician maybe once a week, maybe eight times a week.” If seeing a given artist live becomes a commodity, who needs to acquire a recording? Many real-world musicians have stepped in this direction already: Trent Reznor and his band Nine Inch Nails made the news recently for sharing with their fans more than 400 Gigabytes of unedited, raw concert videos in HD format via their Website. What SL brings beyond this is that in the same time it takes to play an iPod, one can actually be in the concert and experience it as part of the crowd.

The new face of an audience for artists?

If you’re like me, you’ll probably feel skeptical at this point. Experiencing a virtual concert conjures up visions of uninspiring 3D polygons, awkward navigation with a mouse and keyboard and avatars mistakenly rendered half-way through a pillar or a wall. All of this is true. But what is also true is that, despite all the glitches, the feeling of being there is absolutely astonishing. Watching a concert with your screen flushed with a constant flow of text comments from the audience, hearing the sound of clapping and fans calling out to the band with their real voice (if it works for Skype, it does here too) as well as seeing the performer obviously reacting to all this, addressing people by their names, taking song requests—all this leaves one wondering if there is actually anything missing from the real-life experience of music. Technology is constantly improving, and we will soon be able to teleport at will in the middle of an ongoing music video of perfect HD quality. Already, in June 2008, hit UK pop star Kirsty Hawkshaw had the video of her song “Hypoheretic” shot in a virtual world, in “real-time 3D.”

The experience is good for the artist too, it seems. Doubledown Tandino, a well-known DJ in SL, says it’s even better than the real thing “because all the people that are listening love what they’re hearing— else they’d just step out and teleport to the place that does have the DJ they want to hear. The crowd is always much more appreciative and respectful than in RL [Real Life].” How about the audience lacking body language and real-life responses? “It’s replaced by a different sort of energy. It’s about the shared musical experience, blasting the tunes and being locked in great conversation that fills up the night with a great experience for everyone. There is a way to read a virtual crowd by the way it texts or tips.”

An example of an SL venue.

And that is the crux: connecting with the fans creates revenue. SL has its own currency, the Linden dollar $L, and it has an exchange rate with the U.S. Dollar. In other words, the money one makes in SL is real money. In our study of the 57 Djs in the SL Club Vortex, we found that most people tip at least 50$L per DJ set, with an average of 100$L (c. 100 yen). The average tip jar earned per set by a DJ is 1000$L (c. 1000 yen), with peaks at 5000$L (c. 5000 yen). These amounts are smaller than their real-life equivalent, but then nothing prevents you from playing tens of performances every month, as potential venues are just one “teleport” away. “Performing virtually has a number of advantages over RL,” says Paul Cohen, the Tokyo-based brain behind Komuso Tokugawa the BluesBorg, “instant setup, no travel from home studio to gig, and less wear and tear on gear.” Over the past 3 years, Paul/Komuso has played over 800 concerts in SL, topping at more than 40 a month. Even with only a few tens of dedicated fans at each concert who are ready to tip (about 60-70 percent of my gig audiences are regulars), this is clearly not a bad business to get into—one that is reminiscent of Kevin Kelly’s vision of an independent artist needing only 1,000 “true fans” (that will buy anything he/she produces) to reach sustainability.

All this SL activity is starting to reach out too. Real-life companies increasingly hire SL musicians to advertise their brand into the virtual world (for instance, DJ Tandino was contracted by Playboy in 2007). The recording industry itself is said to scout SL for new talents. In August 2008, SL bluesman Von Johin signed what is believed to be the first record deal offered to an avatar, with the independent label Reality Entertainment. Not surprising, says Sho Iwase, music industry expert in Gerson Lehrman Group. “Japan has many examples of artists receiving massive

While record stores exist, the majority of the money made in the virtual music industry is made from live performances.

popularity online through websites like Niko Niko Douga [the Japanese YouTube] and eventually managing to earn themselves a record label contract. Rapbit and Kurikinton Fox are two prime examples.” You start by uploading a video of yourself rapping to an anime theme song and you end up signed to EMI. The transition might be difficult, though, warns Iwase: “Virtual music fans like the musician because he/she is unknown and is “close” to them. Once he/she becomes popular, fans no longer feel needed and tend to move on.” Von Johin’s weekly concerts in SL remain free for now, but his debut album is planned to reach iTunes and Amazon at the end of this year and some compromises may be needed on the way.

This shows that eventually virtual worlds like SL cannot stand alone as a replacement for the current system. “It’s just a tool, and I’m just connecting worlds,” says Paul Cohen/ Komuso Tokugawa. But in the process, blues-singing robots like Komuso are also showing that there are still ways to make a living doing just what music should be about: playing and getting heard. And this is good news, especially for Bruce Springsteen. JI

-

JJ Aucouturier is an assistant professor of Computer Science at Temple University, Japan Campus. He is an expert in audio technology and artificial intelligence, with a background in the music industry. More on jj-aucouturier.info

The article above came from HERE

http://www.japaninc.com/mgz86/real-music-for-virtual-world

------

No comments:

Post a Comment